“If it means I have to get down on the ground and color for a few minutes, I’ll get down on the ground and color for a few minutes. It’s not a question of ‘I’ve got to get you in here, got to get you out;’ it’s really trying to make them feel comfortable.” Liana Hill

CULLMAN, Ala. – Liana Hill is not from around here, and if you talk to her, it’s pretty obvious. A distinct native English accent with a subtle hint of Highlands spice from a sojourn in Scotland makes her an interesting person to listen to on any subject of conversation. But she has a calling to help children in crisis, and talks about her profession with a passion you’ll remember long after you forget the accent.

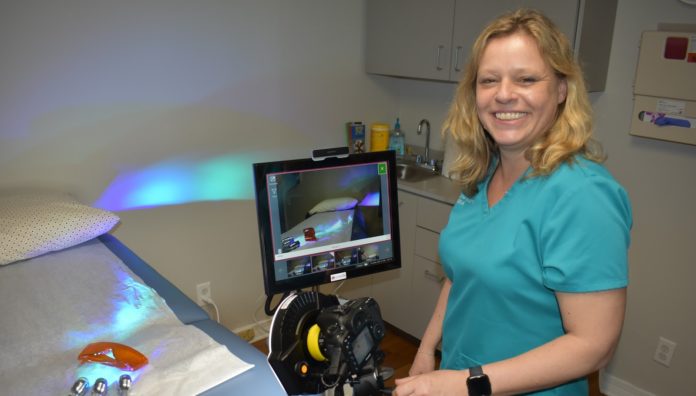

Hill is a forensic nurse with Huntsville-based Crisis Services of North Alabama (CSNA), who comes to Cullman on a regular basis to provide services to the clients at Brooks’ Place (BP) Child Advocacy Center. Here in Cullman, she has a state of the art examination room with all kinds of cool “CSI”-ish stuff like special lights and a serious camera linked to an even more serious computer system. But it’s the person who makes all the toys work. Hill knows how to use the tools, but she also knows how to communicate with victims and their families, as well as prosecutors, judges and juries. Above all, she knows how to help kids.

Hill explained what she does:

“There’s different fields of forensic nursing, but I’m specializing in the forensic nursing where I see patients that have been assaulted. That means that I’m going to collect evidence from them, whether that’s DNA evidence related to possibly sexual assault or strangulation cases, anything with touch DNA. We’re actually looking for DNA evidence,” she said. “But, from the forensic standpoint as well, it’s not just collecting DNA evidence. It’s collecting photographs from a patient’s body, or looking for injuries and showing some consistency or inconsistency with what the patient’s telling us. As a forensic nurse, you can be specialized in looking after pediatrics, adults, adolescents; I’m trained to see 0 and up (all ages).”

Hill has served at BP for three years as a forensic nurse. BP is one of only three child advocacy centers in Alabama that can offer medical services onsite, saving patients the time and expense of having to travel to places like Birmingham or Huntsville to be seen in a timely manner. CSNA is on call 24 hours a day, and even after regular hours, can send Hill or another nurse to Cullman on short notice.

Those who are examined are not just victims. Operating as a neutral forensic expert, Hill will also examine some accused abusers/attackers, finding evidence for or against claims made about the crime or the accused.

The child advocacy center conducts more than 300 interviews per year, and each child is offered a free medical exam to check for unmet medical needs, not just evidence of assault. Exams can help staff identify signs of neglect or other health conditions, and allow them to develop a response plan to do as much for that child as they can. All examinations and testing conducted at BP are free of charge.

BP Executive Director Gail Swafford said, “On the forensic side, yes, we want that, but even more so, we want to make sure that kids are getting medical services that are sometimes overlooked.”

As a nurse who is not a nurse practitioner, Hill cannot diagnose medical conditions, but she can look for signs of health issues and refer the child and family to other medical resources. Almost all of the children who come in, though, have been the victims of some type of assault or abuse. Hill and BP offer them medical examinations that uncover evidence, but in ways that don’t subject them to further frightening and invasive experiences. In this setting, the children and their parents/guardians are given a high degree of control–being able to say yes or no to any proposed procedure–for that very reason: to feel a sense of ownership of their bodies that an assault or abuse may have taken from them previously. For younger children, procedures are explained to parents/guardians in detail, and trained child advocates walk through the process by the child’s side.

Said Hill, “It’s driven by that child. It’s not something like they go to the emergency room and they have to be held down to have an IV or something like that. This is a process, making them feel comfortable, giving them some power of control back, because sometimes they haven’t had that for many, many years.”

Swafford added, “A child is not forced to undergo an exam, especially with a teenager. I mean, they can stop an exam at any time. It’s giving them that power of control back that they didn’t have during an assault. They may not be ready.

“And what we’ve found is, we can do a forensic interview–that’s what we’ve been trained to do. They may not disclose as much to us as they will a medical person, because they feel like if you’re going to the doctor, you can tell a doctor or a nurse anything. And sometimes, they’re actually told more information than we are.”

BP’s waiting area and even exam rooms are not as “medical” as some doctors’ offices, and that’s by design. The presence of toys and age-appropriate decorations helps kids be at ease in an otherwise very uneasy situation.

When you know you’re likely to have to perform a forensic exam on a child, how do you first approach that child?

Hill said, “It all depends on the age of the child, because you’re going to handle different ages differently. But if you’re talking about small pediatric cases, parents, they’re going to have some discomfort. They’re going to have an idea of what that medical exam’s going to involve, and so just letting them know that it’s not a scary exam; it’s more just an examination that’s done while someone’s playing and talking to the child. Because I’m not in there on my own.

“I work very closely with the family advocates here, because I could not do an exam without having somebody else there, looking after the child, making sure that they’re feeling comfortable. And if I’m doing something and that child, maybe their face is saying (they are afraid), that advocate’s going to be right there, watching and seeing what’s going on.

“We bring them into the exam room. We show them the exam room, so they’re not kind of scared. It’s not kind of an unknown: ‘Okay, come down to the exam room now. This is where you’re going to be;’ take them in there.

“And, you know, if it means I have to get down on the ground and color for a few minutes, I’ll get down on the ground and color for a few minutes. It’s not a question of ‘I’ve got to get you in here, got to get you out;’ it’s really trying to make them feel comfortable.”

In cases of sexual assault, teenage girls are often subjected to invasive examinations at emergency rooms, but BP takes each victim on a case-by-case basis and allows him or her control over the degree of examination he or she is comfortable receiving. In some cases, the most important thing a victim needs from his or her nurse is a little knowledge and a very willing ear.

Said Hill, “(It’s) a child being able to talk to someone about the concerns they have medically, but they may not feel that they can talk to anybody else about because it’s sometimes embarrassing or uncomfortable. Talking to a medical professional who’s trained in this specialty; it’s very different from walking into the ER or walking into a doctor’s office. What we’re looking at when we’re looking at injuries, we’re trained specifically to look for certain things. So, even when I’m doing an exam, sometimes I can say to a child something that they’ve probably been thinking about but they don’t want to talk about, because I’m seeing something that’s related to assault or abuse. It’s all about play therapy through a forensic exam.”

Standing alone in the field of forensic nursing

Hill reported that CSNA is the only forensic medical service in the U.S. authorized by the International Association of Forensic Nurses to train nurses in examining all age levels of victims. A recent upgrade in the training procedure–the only one of its kind in Alabama–allows new nurses more opportunity to hone their skills with knowledgeable mentors before having to jump headfirst into traumatic situations, giving them more ability to respond professionally and compassionately to real victims.

Giving victims control

Shared Swafford, “What’s so phenomenal to me is because it is so much geared toward making that patient in control of the examination and letting that patient know, ‘You’re okay.’ And the nurses are trained to talk to them about ‘Your body’s okay,’ because that’s the question when you’re assaulted: ‘Am I ever going to be the same?’ You just have all these ideas in your head.

“It’s all about giving power and control back to that patient and letting them know, ‘This is your body; you’re in control. And we as the associate are trying to impart on these nurses, ‘Pay attention to your patient, because they may not have the ability to say, ‘I want to stop,’ but by looking at them and keying in on their affect–just their face–you can tell they need to stop, they need a break, they can’t go any further. But it’s all about that trauma-informed approach, because again, we don’t want to retraumatize them in any way. So that’s what I like about it: it’s very victim-oriented and it’s all about that person that’s on that table and giving them that control, and helping them feel less vulnerable, I guess.”

The numbers

- In 2017, the most recent year for which statistics are available, BP conducted 307 client interviews, 117 medical exams and more than 1,500 counseling sessions. BP considers those numbers to be fairly consistent.

- Most victims who receive medical exams at BP are between 4 and 8 years old, or between 14 and 17 years.

- 65 percent of BP clients are female; 35 percent are male.

Swafford said of Hill and the nurses from CSNA, “I’m so bought into what they do. Some of the things that they have done have helped improve the lives of these kids and families so much. I can’t even describe what that is, because it’s just so huge. I don’t know what we did without them before.”

Hill said of her experience at BP, “I see the need in this community. It’s huge to be part of it, to be part of Brooks’ Place. You know, they have a great team of individuals that work together to provide care to the families and the patients. I just come in that little bit at the back of it, and just make sure that these patients are okay medically and they receive the care they need. Coming from Huntsville and being allowed to have this space here, to be contracted here to work for Brooks’ Place, has been huge. My passion–I see victims of assault–but my passion is pediatrics, my passion is the kids.

“And just knowing that someone can come in here and talk to me about anything, and I’ll listen, and it doesn’t sound stupid, because you’re concerned about something on your body that you just don’t want to tell someone else about because you think it’s related to a sexual assault–and it might not be–but you’re too scared to tell someone about it; that’s huge for someone, huge for someone to move forward and take that healing away with them.

“I feel honored that they’ve allowed me to move into this space and see the children of Cullman, because there’s a need there. There’s a huge need for the children.”

For more about Brooks’ Place Child Advocacy Center, visit www.caccullman.org or call 256-739-2243.

Copyright 2019 Humble Roots, LLC. All Rights Reserved.