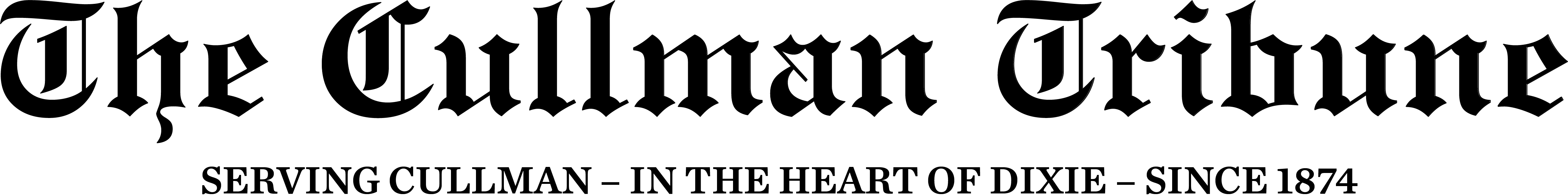

Photos: Earl T. Smith/1956; Smith, originally from Hatton, now lives in Talladega, Alabama.

You know it’s going to be bad when the phone rings around midnight. Instantly awake, Airman 1st Class, Earl T. ‘Buster’ Smith, Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) Tech on call, grabbed for the receiver and his pants at the same time.

“We have a Broken Arrow situation,” said the voice on the other end of the line. Swiftly, Smith dressed, listening to instructions as he slipped into his boots. Ignoring the flapping boot laces he raced out of the room, down the hall and out the front door into a bone-chilling, freezing cold, January night with winds as cruel as needles and a silence that rivaled the grave. People sleeping snuggled in their warm beds in the houses surrounding Smith’s were blissfully unaware that they were in the greatest danger of their lives.

A helicopter awaited him on the tarmac at Seymour Johnson AFB just southeast of the city of Goldsboro, North Carolina. Base Commander Brig. Gen. Joseph H. Moore was already inside. Both men were grim.

At 12:35 a.m. Jan. 24, 1961, an air force plane, ‘Keep 19’ crashed 12 miles north of the air base. It came to rest in a tobacco field just a few yards away from Big Daddy’s Road in the farming community of Faro.

Because Smith actually got the call while the plane, although in distress, was still in the air, he and Moore were the first people to arrive at the site. Fires burned in several spots, whipped viciously by bitter winds. The combined stench of burning flesh and jet fuel was almost overpowering.

When he’d heard the term ‘Broken Arrow’ he’d instantly realized that a powerful B52-G Stratofortress bomber was signaling distress calls while on patrol off the North Carolina coast. By the time the helicopter touched down, it was obvious that the plane had crashed. Later, he discovered that the cause of the crash was leaking fuel in the bay area. “Possibly it could have ignited when they put down their landing gear,” Smith theorized. “The wing sheared off and the plane went into a tailspin.” The plane literally cracked apart in the middle.

As plane crashes go, it was one of the most dangerous events that ever took place over American soil. This particular B52-G, traveling at 700 mph, was carrying a payload in its cargo area that would have shocked Americans, had they known – two 3.8-megaton Mark 39 hydrogen (thermonuclear) bombs – 250 times more powerful than the one dropped on Nagasaki.

These bombs, had they exploded, would have caused the worst thermonuclear disaster in history of the world.

Each bomb would exceed the yield of all munitions (outside of testing) ever detonated in the history of the world by TNT, gunpowder, conventional bombs and the Hiroshima and Nagasaki blasts combined.

Smith estimates that had the devices exploded on impact they would have killed approximately 250,000 people instantly. Estimates are that the fallout would have reached as far as New York City and eliminated most of the eastern seaboard.

Two pilots and one gunner were killed in the crash. In July 2012, the state of North Carolina erected a historical road marker in the town of Eureka, 3 miles north of the crash site, commemorating the crash under the title "Nuclear Mishap."

The memorial does not list the names of the three aircrew who died in the accident, but we are honored to do so her: Sgt. Francis Roger Barnish (35), Maj. Eugene Holcombe Richards (42) and Maj. Eugene Shelton (41).

The other five members of the flight crew, flight commander and pilot Walter Scott Tulloch, co-pilot Richard Rardin, relief pilot Lt. Adam Mattocks, electronic warfare officer Bill Wilson and navigator Paul Brown, were able to parachute out of the plane and were alive and to a large extent, uninjured. Mattocks had already begun walking down the road to find help before Smith’s arrival on the scene. Later Maddox would say that the only problem he had after the crash were the various dogs that challenged him along the dark, deserted North Carolina backroads. When he reached the gate of the military base, he was contested by the guards on duty who knew nothing of the crash. Eventually, he was arrested for stealing the parachute case which he was still wearing. Later, when word got out, he was released and acquitted of all charges.

Back at the site, in a field lit by fires from the burning jet fuel, staring around at the wreckage, an almost paralyzing fear came upon the young EOD officer. “I felt like I was being poisoned by radiation,” said Smith. “I thought I would soon have a heart attack, and I kept telling myself that if I was going to die, I should get as much done as I could before that happened.”

Suddenly, in the distance, he spotted the red flashing lights of an approaching ambulance, “For some reason, as soon as I saw it I began to calm down,” he said.

One bomb’s parachute had deployed. The fact that it landed in a tree helped him to determine its location quickly.

His training took over and he very carefully opened the fuse access door to check the ARM/SAFE switch, which he found to be in the SAFE position. Smith breathed for what seemed like the first time since the phone call had started this sequence of nightmarish events.

He was 24 years old.

Candidates for EOD School are strictly volunteers. They choose to put themselves in harm’s way in one of the most dangerous jobs on the planet. One wrong move, one bad call, one slight tremble of the hand, and in less time than it takes to blink, the area for miles around goes up in a mushroom cloud.

Due to a strict two-man bomb diffusion policy, Smith was required to wait for assistance before going any further after ascertaining that the ARM/SAFE switch was in the SAFE position. When that assistance arrived, he and another EOD team member, Airman 1st Class Joe Fincher, were able to defuse the bomb in a matter of minutes. “It was actually Fincher’s hand which disconnected the last wires,” said Smith, crediting his fellow EOD team members with being part of what would turn out to be the worst nuclear ‘near-miss’ in history. “There were four wires, we had to disconnect two, then wait for three minutes before disconnecting the next part. That is what Fincher did. Another EOD tech, Tolbert Evers, was also with us.”

Before daylight, when higher ranking officers made it to the scene, the EOD techs had already disarmed the first bomb.

The second bomb is quite another story.

It was about two hours before other Air Force personnel; including 3-Star Gen. Walter C. Sweeney, Jr. who was at the time, SAC Commander of the 8th AF, began to show up at the site. Smith and his fellow officers went into official search and identify mode, collecting pieces of the plane and cataloging each meticulously. According to Smith, seven and a half hours after his own arrival at the crash site, a senior EOD officer showed up. Since he outranked everyone present the scene was officially under his command.

Smith explained the protocol, “In this situation, the ranking EOD officer would have had authority over the site, even over the generals present because he was an EOD officer, and the generals might outrank him, but they knew nothing about disarming bombs.”

The search for the other bomb intensified. The crew was there for 86-96 hours before they were allowed to leave in shifts to rest, then report back to the site.

“Parts of the second bomb were never found, including the thermonuclear core or ‘squash’ device,” said Smith. “Although the military bought the land, and released statements to the press indicating that everything was accounted for, I know for a fact that parts of the other bomb were never found.”

According to Wikipedia’s “List of Nuclear Accidents” concerning the second bomb of which Smith spoke, “Most of the thermonuclear stage, containing uranium, was left on site. It is estimated to lie around 55 feet (17 m) below ground. The Air Force purchased the land and fenced it off to prevent its disturbance, and it is tested regularly for contamination, although none has so far been found.”

Of that bomb, this paragraph was included in the special investigation report, “The report provides significant information on Weapon 2. It landed in a free-fall. Without the parachute operating, the timer did not initiate the bomb's high voltage battery ("trajectory arming"), a step in the arming sequence. While the Arm/Safe switch was in the "safe" position, it had become virtually armed because the impact of the crash had rotated the indicator drum to the "armed" position. But the shock also damaged the switch contacts, which had to be intact for the weapon to detonate. While Weapon 2 was not close to detonation, the fact that the physical impact of a crash could activate the same arming mechanism that had kept Weapon 1 safe showed the danger of such accidents.”

Now, still owned by the government, the site is fenced and inaccessible to the public. Four days after this incident, President John F. Kennedy, only four days in office at the time, grounded all flights carrying Mark 39 nuclear weapons over the U.S.

The Goldsboro accident occurred at the height of the Cold War. Kennedy had taken office only four days earlier, and would soon lead the nation through its closest brush with nuclear war, the Cuban Missile Crisis. Moreover, the B-52 involved in the Goldsboro crash was not on a training flight; it was, according to the Department of Defense account, on an "airborne alert" mission, an operation designed to keep U.S. nuclear arms airborne and deliverable 24 hours a day. (www.ibiblio.com)

The official report stated that the T-249 Arm/Safe switch worked exactly as it was supposed to, preventing a nuclear explosion. Nevertheless, the incident deeply worried Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. A few years later, he observed that "by the slightest margin of chance, literally the failure of two wires to cross, a nuclear explosion was averted."

Smith, originally from Hatton, Alabama, joined the Air Force in 1956, straight out of high school. He recalls enjoying being a part of the special EOD unit, noting that it was exciting to him and his fellow EOD officers. “I liked the adrenaline rush,” he laughed.

“They took us in and debriefed us, then told us that the whole thing was top-secret, and reminded us several times that we could get a 25-year prison sentence for talking to anyone about the incident,” Smith explained. “So I had put it out of my mind, never even thought about it anymore.”

In 2014, after a mandatory 50-year interment, the incident was declassified under the Freedom of Information Act.

By doing their jobs, EOD Smith and EOD Fincher, averted an unthinkable disaster. One wrong move and there would have been an explosion that would have changed the United States map.

Smith spoke to outgoing President of the Wayne County, North Carolina Historical Association, Kirk Keller about the incident. “Goldsboro was a hub for the railroads as far back as the Civil War,” Keller explained. “It was an important target for Sherman as he marched toward Savannah in 1864. The railroads put us on the map and the nuclear incident at Goldsboro almost took us off the map.”

Smith’s memories of that night include being in the bottom of a freezing cold, wet, muddy hole, handing pieces of the second bomb up the chain of human hands to the top. “I’ll never forget where I was that night,” Smith laughed. “I’ve never been so cold in my life,” he added.

A humble man, Smith noted several times that he was part of a team. However, he was the first EOD tech on site, and his hands first touched a bomb that under slightly different circumstances might have caused the worst nuclear incident in the world.

Some sites online say that since 1950, there have been 32 nuclear weapon accidents, known as "Broken Arrows." Other data has that number closer to 60, although none were of this magnitude, and not all were over U.S. soil.

According to www.atomicarchive.com, to date, six nuclear weapons have been lost and never recovered.

More

From the National Security Archives/George Washington University/ Nuclear Vault

Document 5: J. M. de Montmollin and W. R. Hoagland, Sandia Corporation, "Analysis of the Safety Aspects of the MK 39 MOD 2 Bombs Involved in B-52G Crash Near Greensboro, North Carolina," SCDR 8-81, February 1961, No classification markings, excised copy

Source: FOIA request

The Goldsboro B-52 crash prompted an investigation by experts from Sandia, Los Alamos, and the AEC's Albuquerque Operations Office (ALO). Subsequently, some of the weapons components were taken to Sandia for further analysis, which led to a detailed report on what happened to both MK 39 bombs during the accident. According to the report, the impact of the aircraft breakup initiated the fuzing sequence for both bombs. For example, on Weapon 1, the crash yanked the safing pins from the Bisch generator which provided electric power to the weapon. Moreover, the lanyards (that General Power had proposed scrapping) actually pulled the safing pins from the weapons. Weapon 1, which landed essentially intact, was in the "safe" position when it dropped, preventing detonation. The T-249 Arm/Safe switch worked exactly as it was supposed to, preventing a nuclear explosion. Nevertheless, the incident deeply worried Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara: a few years later, he observed that "by the slightest margin of chance, literally the failure of two wires to cross, a nuclear explosion was averted."[5]

The report provides significant information on Weapon 2. It landed in a free-fall. Without the parachute operating, the timer did not initiate the bomb's high voltage battery ("trajectory arming"), a step in the arming sequence. While the Arm/Safe switch was in the "safe" position, it had become virtually armed because the impact of the crash had rotated the indicator drum to the "armed" position. But the shock also damaged the switch contacts, which had to be intact for the weapon to detonate. While Weapon 2 was not close to detonation, the fact that the physical impact of a crash could activate the same arming mechanism that had kept Weapon 1 safe showed the danger of such accidents.

The faulty operation of the lanyards worried the analysts. A modification program, ALT 197, was already underway to remove them and the analysts recommended rapid implementation of this change to all weapons in the "MK 15/39 family" involved in the airborne alert program.

Document 6: R. N. Brodie, A Review of the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Safety Program- 1945 to 1986, Sandia National Laboratories, SAND86-2955, February 1987, Secret/Restricted Data, Excised copy

Source: Mandatory declassification review request

This demanding and technical Sandia nuclear safety study focused on the impact of changing weapons design, major accidents, and the weapons systems safety organization at Sandia Laboratory. Before the introduction of sealed-pit weapons, safety was achieved in a "visible and almost absolute manner by ensuring that the fissile material was kept physically separate" from the high explosives. But when sealed-pit weapons entered the arsenal, safety policy did not adequately or immediately address the problems they raised, leading government officials to take "frantic" efforts to remedy some of them.

Several accidents later — Brodie provides an overview of the major episodes of the 1960s, including the Jonesboro accident — a "new" approach was taken and basic criteria for nuclear safety were reconsidered. That review established a new standard: that in either normal or abnormal environments (in the event of an accident), the annual risk of detonation would be no greater than one in a million for an arsenal of ten thousand weapons or more. To mitigate risks, safety experts developed new design safety concepts and techniques to reduce the danger of contamination by using "insensitive high explosives."

Whatever was done after 1968 was not enough because in the mid-1970s Sandia experts identified new problems, notably that some weapons on continuous alert might be unsafe in "abnormal" environments. A formal review of stockpile safety found that for all weapons it was not possible to predict the "probability threshold for a nuclear detonation" in certain "abnormal environments." It was not even possible analytically to show "how 'unsafe' a weapon was." That level of uncertainty could lead to the conclusion that the whole stockpile had to be replaced, but senior officials concluded that because an accidental detonation had not occurred it was acceptable to "do more studies" and gradually improve the situation as better weapons became available. Experts at Sandia found this "laissez-faire" approach disturbing and prepared new studies identifying which weapons should be retired or retrofit and modified because of "nuclear detonation safety concerns." Four weapons — the B-28 bomb, Nike-Hercules, Genie, and the B53 — needed to be addressed on a "time urgent" basis. The Defense Department accepted the recommendations in principle in 1979, which led to changes that put the stockpile in an "improved safety position." Nevertheless, the same four weapons remained a concern.

Copyright 2016 Humble Roots, LLC. All Rights Reserved.