We believe we are all one human family created by God, born equally, and have a duty to help one another.”the first operating philosophy and guiding principle for the Nyaka AIDS Orphans Project

CULLMAN – On Friday evening, March 4, Rachel Dawsey, director of the North Alabama Agriplex, hosted a very special guest. Twesigwe Jackson Kaguri, founder and director of the Nyaka AIDS Orphans Project in Uganda and globally-acclaimed humanitarian visited Cullman to share his story and speak about the success of Nyaka schools and his projects. Over the weekend, Kaguri also spoke at the Cullman Rotary Club and at Cullman First United Methodist Church.

The Nyaka AIDS Orphans Project’s mission is to work for the HIV/AIDS orphans in rural Uganda to end the cycle of poverty and hunger by providing education, healthcare and community assistance.

Over 1.1 million HIV/AIDS orphans have been left behind after their parents lost their battles with the virus. In rural Uganda an entire generation of men and women are gone and their children left with the hopes of aunts or uncles to care for them. All too often, those distant relatives are gone, too. Grandmothers or elderly women in their villages are able to care for some of the orphans. For many of the children, no one comes to care for them.

This is where the Nyaka Project comes in. An estimated 43,000 HIV/AIDS orphans currently receive services through the organization. Their services include free education and nutritional aid for the children.

Currently, Nyaka operates two primary schools for the orphans with its first having opened in 2003 in the small village of Nyakagyezi. At the primary schools, 463 students are receiving a free education this year. Typically, Ugandan schools require steep fees for attendance, but the Nyaka schools provide “textbooks, uniforms, shoes, two meals every school day, medicine and scholastic materials for free.”

A Nyaka student’s education does not end there, as “they are guaranteed an education until they achieve their academic goal,” whether that be attending university or vocational school. Both forms of higher education offer endless possibilities to end poverty, and Nyaka is committed to helping their students achieve whatever goals they seek.

The Nyaka Aids Orphans Project provides counseling and medical care in addition to its educational guidance. The continuing education is stressed as “without a secondary and high school education, girls are more likely to marry while young, run away to the city to get a low wage job or become sex workers. Boys also end up working low paying jobs and never escape the cycle of poverty. An important part of our mission is to ensure that our students go to secondary and high school. A strong education is our greatest hope for our students to begin envisioning a life beyond the HIV/AIDS pandemic.”

Common in Ugandan culture is for the younger generation to care for its parents. With no one to care for the elders who have lost their children to the AIDS crisis and with many of those elders now being tasked with raising their orphaned grandchildren, Nyaka’s Grandmother Programs empower the women with their 92 self-formed Granny Groups which serve 7,004 grandmothers in the rural communities. The grandmothers, while given guidance and support by the Nyaka staff, are the decision makers who “determine who among them receives donated items, attends training, micro-finance funds, homes, pit latrines and smokeless kitchens.” The collaborative effort of the grandmothers builds a support system whose help cannot be quantified.

Nyaka also provides many community projects including its Desire Farm, clean water facilities, healthcare clinics and libraries.

The Nyaka AIDS Orphans Project’s founder and director, Twesigwe Jackson Kaguri, escaped the crippling poverty of Uganda after being born and raised in it. As a student at Columbia University in the 1990s, Kaguri studied Human Rights Advocacy, having traveled far from the devastating destitution of his home village of Nyakagyezi.

He married, and, with his wife, was saving money for a down payment on their first home. Yet, in 2001, Kaguri left America and returned to his native land. What brought him back was the same thing he escaped.

Kaguri’s parents expressed a strong desire for their children to receive an education for as long as he can remember. Their desire was two-fold. His parents, who had never attended school themselves, wished for their children to break the cycle of poverty that was common in their area. Additionally, his parents knew they would be rewarded in their investment by being cared for in their later years. “We were not going to school for ourselves. We were going to school for our mom and for our dad. For our community and for our grandparents.”

However, in Kaguri’s home village in Uganda, an education for just one child was a difficult goal to attain due to the steep fees levied by the schools. Against all odds, his parents’ dream was for all five of the children to go to school.

Sacrifices were made to ensure their education. The family went without the nourishment of meat as their animals were sold to meet the financial burden of the schooling. In their village, as with most in Africa, education was not free and came at a hefty cost. The medical needs of Kaguri’s parents were often not met to help finance their children’s schooling. Scarcity became normal as his father would purchase one pencil which he would break into fifths so that each of the five children would have a writing utensil for school.

After years of walking fifteen miles to school each day, Kaguri was afforded the opportunity to study at Makerere University in Kampala. There he was first introduced to the concept of basic human rights. When his instructor spoke of every human being having the right to an education, Kaguri expressed his puzzlement. Human rights were a very foreign concept which contradicted the realities of life in Nyakagyezi.

He explained, “It was at my university that I first read this statement. ‘Every human being has a right to education.’ My hand went up quickly and I asked, ‘Every human being?’ and my professor answered, ‘Yes, every human being.’ Then, my people are not human beings if everyone has these rights and my people do not.”

He continued, “It was then that the childhood memories (came) of how unjust my community was. How unjust that my mom had suffered, abused and beaten by my own father, and she still cooked for him. How unjust that we had no food and walked fifteen miles to school on an empty stomach. All of that injustice came to me.”

In learning of these basic human rights, including education, health care, food, shelter, respect and love, and seeing the lack of them in his own community, Kaguri found his passion.

From Africa, Kaguri traveled to the United States to study at Columbia University. While there, his eldest brother died of the AIDS virus in 1996, leaving behind three children for his youngest brother to raise. The loss was a devastating blow to the entire family, emotionally and financially. His brother, 14 years his senior, was a second father to Kaguri and was mourned deeply after his death.

“I saw him taking care of people. I saw him mentoring others. He was like a dad to me.”

Less than a year later, his eldest sister lost her battle to the virus. Her son, born with the AIDS virus, would need cared for as well.

Character cannot be developed in ease and quiet. Only through experience of trial and suffering can the soul be strengthened, vision cleared, ambition inspired and success achieved.”Helen Keller

Through his grief, Kaguri found vision.

“It was then that I packed my bags at Columbia University, left my job opportunity at the United Nations and went back to Uganda so that my nieces and nephews would get an opportunity to go to school and have a place to sleep. I went back to be with my nephew who was born with HIV and I still wanted to give him a childhood, a chance to enjoy his childhood for the few years he would be living.”

In 2001, he founded The Nyaka AIDS Orphans Project. His nieces and nephews were not the only orphans devastated by the effects of AIDS. His homeland was riddled with these children with no hope and no future.

Kaguri returned home, and with the money he and his wife had saved for their future, he built the first Nyaka school. The first school changed the face of the village it served. It changed the lives of the orphaned children and the orphaned grandmothers.

Kaguri tells the story of a young girl attending a Nyaka school who delighted in her education. Eager to learn, she took great pride in her school uniform, painstakingly keeping it as clean and pristine as possible. The young girl, born with AIDS, grew sick from the virus, and nearing her death, she pleaded to be buried in her beloved school uniform. Her grandmother explained that she would be buried in a lovely dress and not the uniform. But the girl insisted, explaining she wanted to meet Jesus wearing what she wore when she was happiest in this life. Her happiest days, she said, were spent in her Nyaka school where she was taught, loved and respected. The young girl died. She was buried in her school uniform.

Kaguri was awarded the 2015 Waislitz Global Citizen Award, has spoken before the United Nations and was named a 2012 CNN Hero for his tireless efforts on behalf of HIV/AIDS orphans. He is also an author, writing of his journey to bring his vision to fruition in “A School for my Village” and “The Price of Stones.” He shares his stories in two children’s books as well.

Kaguri notes that the children in his schools are no different than the children in our Cullman community. They are all children of God. They all have the basic human rights to be loved and respected, to be educated, to have nourishment and to have shelter.

To help provide those basic human rights to the orphans and to learn more, please visit www.nyakaschool.org.

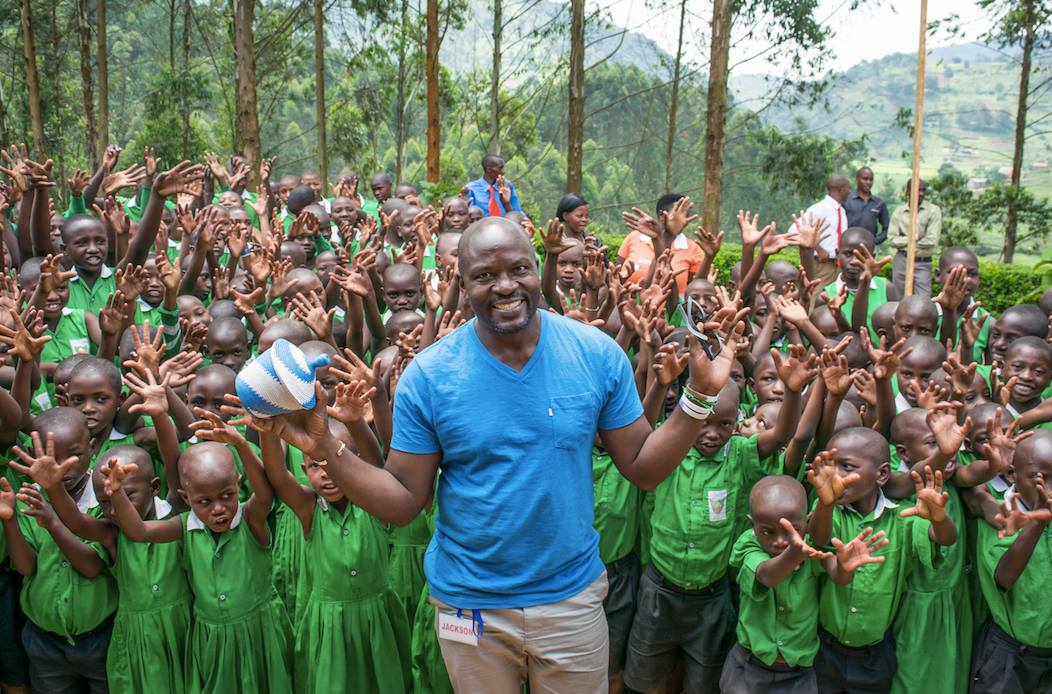

Photo shows Twesigye Jackson Kaguri with some of the students in Uganda.